~by KENNETH KNAPMAN

First Printed and Published by the Workers’ Resource Centre (2000)

170, Wandsworth Road, London, SW8 2LA

All rights reserved, 2000

*******************************************

Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Chapters

The Trade Unions (an early history)

The New Unionism of 1829-34

The Socialist Movement

Chartism

The Co-operative Movement

The New Spirit and New Model Unions

The International

The New Unionism of 1880-1900

The Workers Offensive (1910-14)

The First Imperialist War Years

The Post War Crisis

The 1926 General Strike

Bibliography

******************************************************

FORWARD

Workers’ Resource Centre is very pleased to publish this Short History of the Working Class Movement in Britain up to the 1926 General Strike. Kenneth Knapman wrote the Short History in 1992.

While our historicism begins from the present, and the events in history must be seen from the perspective of the need of the working class at this time to end their marginalisation and de-politicisation and to go for socialism in Britain, it is also necessary to analyse what is stopping them from doing so. A history of the working class movement is one resource, which can be utilised from this standpoint, to examine what was the old philosophic conscience in order to settle scores with it. We hope that readers will find in this Short History such a resource. Readers will be able to draw their own conclusions from the historical traditions of the British working class, one of the oldest, most organised and practical. They will be able to appreciate, as Karl Marx discovered, that in the working class, the modem proletariat, the bourgeoisie has above all else produced its own gravedigger. The class struggle between these two major classes is the basis of the motion, change and development in society. However, Marx also analysed that it is this struggle, which will give rise to the working class constituting itself the nation and establishing socialism. To carry forward the historical traditions of the working class in today’s conditions, in our view, means taking up the task of giving that socialism a content, to give a programme and a vision for the line of march of the working class to this new society, to socialism.

This is the challenge of the working class today, just as it was the challenge in their conditions of the working class in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Workers’ Resource Centre July 15, 2000

INTRODUCTION

EVERY SO OFTEN, as History has shown, the Working Class Movement has had to regenerate itself while trying to operate under the Capitalist System. Today renewal has as much bearing as ever. It is essential because of the offensive against the movement in recent history.

Overall, with the collapse of Eastern Europe, and the remnants of Socialism there, it is necessary to see that the still young movement, despite setbacks, inevitably renews itself. Like the mythological Phoenix it rises again from its ashes to continue with life afresh.

The movement in Britain, affected by the class struggle, has had to move quantitatively and qualitatively making its aims ever higher but has never ultimately resolved the basic class question in Britain in favour of the working class. It is for this reason that zigzags in the movement are bound to happen.

What I have tried to show in this outline, is that the movement has had to become ever more political. The integration, of politics with the working class movement both in theory and practice is of prime importance.

Ken Knapman, Birmingham 1992

CHAPTER ONE

THE TRADE UNIONS

(An Early History)

FROM THE EARLIEST times workers have formed associations to defend their rights and interests against their employers. As they developed as a CLASS, organised resistance against capitalist exploitation and oppression was essential in order to fight for the unity of the working class and to organise to end the system of exploitation of man by man. Socialism has become the ultimate goal under the Capitalist System.

The British Working Class is rightly proud of and loyal to its great traditions of militant organisation, determined and heroic struggle, all of which have characterised its history.

In the earliest days, whatever they may have been called, there were nation-wide organisations like the Great Society of the Fourteenth Century or local Craft bodies like the Yeomen Gilds. These were in essence the earliest forms of unions.

Economic advancement, at first hindered the formation of permanent combinations among the JOURNEYMEN of the middle ages. Certain classes of skilled manual workers, who had no chance of becoming employers, do appear to have succeeded in establishing long lasting combinations. Nevertheless, the Industrial Revolution changed things making wider and more formidable combinations possible.

The partly deliberate and partly natural concealment and secrecy of Trade Unionism of the eighteenth century makes it next to impossible to write History. The members of the earliest clubs were the skilled. Unskilled workers, if they had any such societies, have left no traces of them in history.

A glimpse of activity in 1718 was where a proclamation against unlawful clubs in Devon and Somerset complains about how great numbers of wool combers and weavers had illegally presumed to use a common seal. The proclamation complains about how they tried to ‘Act as bodies Corporate’ by making and unlawfully conspiring to execute certain by-laws or Orders, whereby they pretended to determine who had the right to the Trade, what and how many Apprentices and Journeymen each should keep at once. When the Masters would not submit they fed them with money till they could again get employment in order to oblige their Masters to employ them for want of other hands.

In 1754, 300 Norwich Wool Weavers, desiring to obtain an increase in wages, retreated to a hill three miles away from the town and built huts. They lived there for six weeks supported by contributions from fellow workers.

By 1721 the Journeymen of Tailors of London had a powerful and permanent union.

When the capitalist builder or contractor began to supersede the master mason, master plasterer etc., this class of small entrepreneurs had again to give place to a hierarchy of hired workers, TRADE UNIONS in the modern sense, began to arise.

The TRADE UNION was the successor of the Guild. Both institutions had arisen “under the breaking up of an old system.”

From the moment that to establish a given business more capital is required than a Journeyman can easily accumulate within a few years, guild-mastership – the mastership of the masterpiece, becomes little more than a name. Labour and skill are like commodities. Skill has a value, but skill only has a value if it is sold, hired out to capital. Here you have the opposition of interests between capital and labour. Labour groups together and organises the TRADE SOCIETY.

Industrial society is still divided vertically trade by trade, instead of horizontally between employers and wage earners. It is the horizontal cleavage, which would transform the organisation of petty and narrow-minded craft mentality of the skilled into the modem Trade Union Movement. The pioneers of the Trade Union movement were not the trade clubs of the town Artisans but the extensive combinations of the West of England Woollen workers and Midland framework knitters.

THE COMBINATION ACTS

The Necessity for Workers’ Rights and Organisation to develop empowerment and Opposition.

The Necessity for Workers’ Rights and Organisation can be borne out of history where persistent Trades Union legislation, mainly by Conservatives, has repeatedly attempted to undermine the workers’ capacity to act.

History has shown an uninterrupted series of legislative Acts affecting Trades Unions.

Right from the early days of feudal England the Ordinance of Labourers 1349 and the Statute of Labourers 1351 attempted to suppress sources of wage inflation by banning workers organisation, creating offences for any able-bodied person that did not work, and fixing wages at the time of the great plague and after to pre-plague levels.

An endeavour by the ruling class was made to make even economic resistance impossible. The act against illegal oaths passed in 1797 against the “Nore Mutineers” was used to break up existing Trade Unions;

Nineteenth century Britain recognised the now established post Industrial Revolution class division society where the class relations of production were clear. The Master and Servant Act 1823 and subsequent updates stipulated that all workmen were subject to criminal penalties for disobedience, and calling for strikes was punished as an “aggravated” breach of contract. The capitalist accumalation based on suppressing the claim on value of the product, was not going be allowed to impede profit by collective organisation.

Parliamentary legislation and consolidation of capitalist laws can be seen throughout history. The most infamous were the Combination Acts. The Combination Act 1799 was an Act to prevent capitalist notions put into practice for unlawful combinations of working people that, prohibited trade unions and collective bargaining by British workers. The Act received Royal Assent on 12 July 1799. An additional Act was passed in 1800.

The 1799 and 1800 acts were passed under the government of William Pitt the Younger against strikes. Collectively these acts were known as the Combination Laws. The legislation drove labour organisations underground. Sympathy for the plight of the workers brought repeal of the acts in 1824, political actions inside and outside of Parliament including by Chartist reformer, Francis Place played a role. However, in response to the series of strikes that followed, the Combinations of Workmen Act 1825 was passed, which allowed labour unions but severely restricted their activity.

The 1825 Act followed on from the Combination Act 1799 and the Combination of Workmen Act 1824. The 1824 Act repealed the Acts of 1799 and 1800, but this led to a wave of strikes. Accordingly, the Combinations of Workmen Act 1825 was passed to reimpose criminal sanctions for picketing and other persuasive methods used to cause workers not to work. The laws though, even made any combinations or unions pressing for wage increases or change working hours illegal.

Yet changing laws and the struggle to do so forced changes. The 1825 Act was recommended for amendment by the majority report of the Eleventh and Final Report of the Royal Commissioners appointed to Inquire into the Organisation and Rules of Trade Unions and Other Associations. It was wholly displaced by the Trade Union Act 1871.

Trade Union Act 1871 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which legalised trade unions for the first time in the United Kingdom. This was one of the founding pieces of legislation in UK labour law, though it has today been superseded by the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992.

The Conservative Prime Minister, the Earl of Derby, set up a Royal Commission on Trade Unions in 1867. One worker representative was on the commission, Frederic Harrison, who prepared union witnesses. Robert Applegarth from the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners was a union observer of the proceedings.

The majority report of the Commission was hostile to the idea of decriminalising trade unions. Frederic Harrison, Thomas Hughes and the Earl of Lichfield produced their own minority report, recommending the following changes in the law:

- Combinations of workers should not be liable for conspiracy unless it would be criminal if committed by a single person.

- The restraint of trade doctrine in common law should not apply to trade associations.

- All existing legislation applying to unions specifically should be repealed.

- All unions should receive full legal protection of their funds.

When Gladstone’s government came to power, the Trade Union Congress campaigned for the minority report to be adopted it was successful.

The Provisions of the Act were:

Section 2 provided that the purposes of trade unions should not, although possibly deemed to be in restraint of trade, be deemed unlawful to make any member liable for criminal prosecution.

Section 3 said the restraint of trade doctrine should not make any trade union agreements or trusts void or voidable.

Section 4 stated that any trade union agreements were not directly enforceable or subject to claims for damages for breach. This was designed to ensure that courts did not interfere in union affairs.

However the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1871 was passed at the same time, which made picketing illegal. This was not repealed until the Conspiracy and Protection of Property Act 1875.

The Act was fully repealed by the Trade Union and Labour Relations Act 1974.

During the reign of this anti-union reign of terror it gave birth to real trade unionism. Huge strikes or “turnouts” as they were called took place. The Scottish Weavers in 1812; the Lancashire Spinners in 1818; the North East Coast Miners in 1810; Scotland 1818 and South Wales 1816 (including the Ironfounders, they succeeded in defeating a wage reduction). The advance of unity through these bitter years saw the emergence of the first complete national unions. The Calicoprinters, The Friendly Society of Ironfounders, the Papermakers and the Ropemakers were these national unions.

Without the struggle there would have been no room for the pushing through of a Bill repealing the Combination Laws.

The repeal of the Combination Act seemed to have done nothing but to prove the futility of mere sectional combination (due to the commercial slump of 1825). The emancipated combinations were no more able to resist reductions than the secret ones had been. Working men turned back again from Trade Union action to the larger aims and wider character of the radical and socialist agitations of the time with which from 1829 to 1842, the Trade Union Movement had become inextricably entangled.

Engraving of events at St Peter’s Fields, 1819

The Peterloo Massacre (or Battle of Peterloo) occurred at St Peter’s Field, Manchester, England, on 16 August 1819, when cavalry charged into a crowd of 60,000–80,000 that had gathered to demand the reform of parliamentary representation.

In the next period we were to see the development of the Trades-Union, which represented NEW UNIONISM. Trade Union or Trade Club represented old unionism.

The ideal at which the Trades Unionists aimed was a complete union of all workers in the country in a single national trades union.

CHAPTER TWO

THE NEW UNIONISM OF

1829-34

Just before this period it is appropriate to say that the Lancashire Spinners struggles of the mid-twenties had a consequent development of organisation. A number of trades agreed to form a General Union of Trades, or philanthropic society that became known as the PHILANTHROPIC HERCULES (presumably intended as a legal cover because of the Combination acts). This was the essence of the idea or one big union.

It was in Lancashire that the first outstanding trades union leader appeared, JOHN DOHERTY. He was the moving spirit in a conference of English, Scottish and Irish textile workers held in the Isle of Man in 1829 at which the GRAND GENERAL UNION of the UK was set up. Despite of its name, it appears to have been a union of cotton spinners only.

In 1830 Doherty became secretary to the NATIONAL ASSOCIATION for the PROTECTION of LABOUR. This was the first Trades Union or Union of Trades, as distinct from organisations catering for one section of the workers only.

1831 saw the NATIONAL UNION OF THE WORKING CLASSES, (formed by William Lovett to support the REFORM BILL and with others, in London, became the METROPOLITAN TRADES UNION, to which many unions affiliated.

In 1833 the OPERATIVE BUILDERS UNION was formed out of a number of craft unions reaching a membership of 40,000 mainly around Manchester and Birmingham. Early in 1834 it merged into the GRAND NATIONAL CONSOLIDATED TRADES UNION.

At this time Radical politics were on the agenda and given great attention to by radical newspapers such as “Voice of the People.” They gave attention to the repeal of the union with Ireland and the progress of revolution on the continent.

The Owenite newspapers towards the end of 1833 were full of references to the formation of a General Union of the Productive Classes.

ROBERT OWEN, the Utopian socialist, gave a speech to the OWEN societies of 6th October in 1833.

Robert Owen

“I will now give you, ” he said, “a short outline of the great changes which are in contemplation, and which shall come suddenly upon society like a thief in the night …It is intended that national arrangements shall be formed to include all the working classes in the great organisation, and that each department shall become acquainted with what is going on in other departments; that all individual competition is to cease; that all manufacturers are to be carried on by National Companies … All trades shall first form association of lodges to consist of a convenient number for carrying on the business… all individuals of the specific craft shall become members.”

Immediately after this we find in existence the “GRAND CONSOLIDATED TRADES UNION in January 1834. OWEN was its chief recruiter and propagandist.

THE TOLPUDDLE MARTYRS

Owen’s G.T.C.U. was to come into conflict with the law with the conviction of Six Dorchester Labourers in March 1834 for the mere act of administering an oath. The sentence was seven years transportation. A protest of nation-wide dimensions supported by unions in the north took place over a quarter of a million signatures in a petition were collected for their release and the agitation culminated in London’s first monster working class demonstration, where they marched to Copenhagen Fields near King’s Cross. The building trades struck work to take part. There were no immediate results, but in 1836 the sentences were remitted and the men returned home.

The fall of the G.C.T.U. was marked by the London Tailors’ strike. The strike led to a General G.C.T.U. strike involving 20,000. Funds were burdened and a levy on members taken. Other smaller cities shook the credit of the Grand National. The executive attempted in vain to stem the torrent of strikes by publishing a, “Declaration of the views and objects of trades unions” in which they deprecated disputes and advocated what would now be called Co-operative production by associations of producers. They gave effect to this declaration by refusing to sanction the London shoemakers’ demand for increased wages on the grounds that it was opportune. The decline the union was as rapid as its growth and in August 1834 a delegate conference decided to dissolve the union.

CHAPTER THREE

THE SOCIALIST MOVEMENT

SOCIALISM is a system free from Capitalism, a system run by those that PRODUCE THE WEALTH of society and are not hindered by the multi-millionaires and billionaires who have historically exploited the labour of workingmen and women. It is a society free of exploitation of man by man based on, “from each according to his ability to each according to his work”. Socialism is where the factories, mines, workshops and property are in the hands of the majority of the people, where the Working Class controls production and distribution. Socialism is a system where there is no crisis, no unemployment and no inflation. It is where production is geared to the material and cultural needs of the people as a whole and not to the profits of a few. It is a system that cares for the sick and needy and respects old age and also looks after the future of the youth such as with the provision of education to a high standard.

Socialism is the aspiration of the workers, who, in their heart of hearts, desire fairness, equality, freedom and democracy.

Socialism has been a movement of the people for an ultimate political goal for centuries. It has come up at various times in English History (for instance) before modern times.

In every period there have been those that have held radical thinking and have put forward ideas of running society for the whole of the people, for equality amongst men and women and have spoken of the Class Struggle between the Rich and the Poor.

There have been movements amongst the Slaves of ancient times led by such people as Spartacus the Gladiator against the Roman slave-owners. In Mediaeval times there were the Levellers and there were many leaders of the Peasant uprisings in Feudal Britain. There have been movements amongst the workers against Capitalism which have put forward demands for change, for political rights, for partial demands like the “People’s Charter” and the Chartist Movement in the last century.

Socialists and Trades Unionists have formed Socialist Parties and Socialism has been enshrined as an aim in the constitutions of practically every Trade Union in Britain.

Socialism, as a doctrine, has known many forms. Sometimes trends have arisen to oppose its development in the name of socialism. There was even “Feudal Socialism” which developed at a time when Capitalism replaced the Feudal System and there were aristocrats that warned Capitalism of its impending doom by the rising working class. This “Socialism” was a reactionary ideology to try and stop history advancing.

There was Bourgeois Conservative Socialism, which told the workers that society should be left to the capitalist masters who would somehow become benefactors.

There was Petty Bourgeois Socialism of the middle strata and also Utopian Socialism, that of ROBERT OWEN, FOURIER and SAINT SIMON. The Utopians built model factories to prove to the capitalists that if they gave workers better conditions, education, less hours of working etc. that their productivity was better and so the ideal system should copy such experiments.

But capitalism as a whole, terrified of such notions, only too quickly used its power to crush the dreams of the Utopians. As a reminder Robert Owen’s model factory at New Lanark still stands today as a museum.

New Lanark Cotton Mills

The movement of socialism always advances and it was KARL MARX, the founder of SCIENTIFIC SOCIALISM, who proved the inevitability of the socialist system and that the revolutionary overthrow of Capitalism was the only path.

Karl Marx

“The class struggle leads to the Dictatorship of the Proletariat”, says Marx. Thus socialism reached its conclusion in a logical and analytical way, and society could progress because social development is a scientific phenomenon.

Marx had laid bare the essence of the contradictions in society and proved that the class struggle was the motive force of history. The strategy and tactics needed to be worked out and so Marx and Engels wrote The Manifesto of the Communist Party. All that was needed was to carry out the programme.

The workers did it first of all in the Paris Commune of 1871 and again in 1917 led by Lenin in Russia and in various places since then. Despite Socialism developing to a system in operation as occurred in the Soviet Union for many years, the development of Socialism has gone forward and gone back. We know that the fall of Eastern Europe and Albania as well meant that Socialism, as a system in the world, once again was set back in the 1990’s, but it always inevitably rises again as a more advanced system in future.

Socialism has its origins as an independent movement, separate and from without of the working class movement, just as the Working Class Movement has had its separate development.

The workers, in the past, themselves have only really been able to achieve Trade Union consciousness on their own as a class though it tends towards Socialism.

The Working Class Movement is like a ship on the sea and Socialism is like the land on the distant horizon. The ship will go in and out and grope in the dark and encounter many obstacles. It will probably eventually reach the land but, with a compass on the ship, it will reach the land more quickly. Working class politics and the Socialist ideology is like the compass in the Working Class Movement headed for Socialism; it is the INTEGRATION OF THE TWO MOVEMENTS.

The WORKING CLASS MOVEMENT, (the most important organisation having been the Trade Unions) and the SOCIALIST MOVEMENT, two INDEPENDENT MOVEMENTS being integrated has always been an imperative. It is this integration, which the bourgeoisie has always opposed in order to retard the movement, to slow it down. It is here that we must address ourselves. The capitalists call it “keeping politics out of the unions,” what they mean is keeping out working class politics and keeping in bourgeois politics.

CHAPTER FOUR

CHARTISM

The Chartist political movement (1837-48) was not of a trade union character, even so, trade unionists played an active part in it. The shock troops of Chartism were the textile factory workers and the miners. The former unions favoured by overwhelming majorities the turning of the Lancashire General Strike of 1842 into a political rising for the charter.

Chartists played a leading part in the formation of the first national coalfields organisation, the MINERS ASSOCIATION in 1841. But Chartism tackled too late the vital problem of rooting itself firmly in the relatively strong craft unions.

The stronghold of Chartism lay in the industrial north but ideological origins were from London. The Artisans and skilled craftsmen in London, led by such people as WILLIAM LOVETT, were the pertinent radicals. They were to set up the LONDON WORKING MEN’S ASSOCIATION in June 1836 as a political and educational body intended to attract the “Intelligent and influential portion of the working classes.” It was radical and Owenite in outlook.

In February it drew up a petition to parliament in which were embedded the six demands that afterwards became known as THE PEOPLE’S CHARTER. They were:

• EQUAL ELECTORAL DISTRICTS

• ABOLITION OF THE PROPERTY QUALIFICATIONS FOR MP’S

• UNIVERSAL MANHOOD SUFFRAGE

• ANNUAL PARLIAMENTS

• VOTE BY BALLOT

• THE PAYMENT OF MP’S

Frederick Engels declared that the six points were “sufficient to overthrow the whole English constitution, Queen and Lords included.” “Chartism,” he wrote, “is of an essentially social nature, a class-movement. The `six points’, which for the Radical bourgeoisie are the end of the matter… are for the proletariat a mere means to further ends. `Political power our means, social happiness our end’ is now the clearly formulated war-cry of the Chartists.”

In the spring of 1838 the six points were drafted into the form of a Parliamentary Bill and it was this draft, which became the actual Charter.

The Chartist movement was formally launched at a vast meeting at Newhall Hill, Birmingham, on August 6`” 1838.

There were three distinguished groups; the right wing was led by LOVETT and ATTWOOD, the centre by the dynamic figure of FEARGUS O’CONNOR and the left wing by BRONTERRE O’BRIEN in the early stages and later JULIAN HARNEY and ERNEST JONES.

FEARGUS O’CONNOR had the support of the great majority of the industrial workers, the miners and the ruined and starving hand workers of the North. He was an Irishman, nephew or one of the leaders of the Rebellion of 1798, nurtured on the Irish revolutionary traditions. He was a one time Irish MP and started the famous paper, important in the movement, THE NORTHERN STAR.

O’Brien, Harney and Jones never had the popularity of O’Connor, but were clearer politically. O’Brien was considerably influenced by the ideas of the Co-operative and Owenite socialism. Harney and Jones were younger men who came into the movement when it was already in decline. They both held views in common with KARL MARX, with whom they were closely associated, when he came to live in England in 1848.

During the winter of 1838 collections of petition signatures had begun, the Chartist Convention in February 1839 showed that only 600,000 had been collected. The criticism stimulated activity so that by July 12th it had 1,280,000 signatures.

On July 4th, a body of police, specially imported from London, attacked a meeting at the BULL RING Birmingham with exceptional brutality. The workers rallied and drove the police out of the Bull Ring and it was not till some days later that order was restored in the city, and that was after soldiers had been used to assist the police. The outrage spread rapidly over the Birmingham news and there were a number of violent clashes in Glasgow, Newcastle, Sunderland and Lancashire towns. On July 5th Lovett was arrested.

Hansard Records the Birmingham Bull Ring Riots

Battle of the Bull Ring

The petition was rejected after being debated in parliament. More arrests followed. There were plans for an insurrection, many details of which have never been available. There was also an insurrectionary committee of five.

There was a rising in South Wales where thousands of armed miners, led by JOHN FROST, marched. The miners had been assembled on the night of November 3rd 1839 at Blackwood on the Rhymney. Others from Pontypool and Nantyglo were to meet up with them at Risca, but inexperience of the leaders led this rendezvous to fail. The Chartist force that arrived in Newport numbered some four thousand. They were fired upon by troops concealed in Westgate Hotel. Ten were killed and about fifty were wounded.

Soon after all the Chartist leaders were arrested (in all about 490 were arrested) the movement was forced underground. As the leaders came out of gaol a slow revival began.

In the revival THE NATIONAL CHARTIST ASSOCIATION was formed in July 1840. The N.C.A. was the first real political party of the working class. It went far in trying to remove one of its main weaknesses – the Trade unions and built Chartist groups within them. The attempt was partially successful.

O’Connor was released in August 1841 and preparations were made for a second petition, which took into account poverty. It demanded higher wages, shorter hours and factory legislation.

The capitalist crisis had intensified and unemployment had risen and there were consequent wage reductions. 3,315,000 people signed the second petition nevertheless it was rejected by Parliament in May 1842. Strikes broke out all over Lancashire against the wage reductions.

In the second week in August the strikers turned a casual strike in Ashton-under-Lyne into a strike for the Charter. Immediately it spread. Manchester came out, and then it went over into Lancashire, Yorkshire, Cheshire and the Potteries, Warwickshire and into Wales. The Scottish Miners came out. A trade union conference decided by an overwhelming majority:

“That it is our solemn and conscientious conviction that all evils that afflict society, and which have prostrated the energies of the great body of the producing classes, arise solely from class legislation; and that the only remedy for the present alarming distress and widespread destitution is the immediate and unmutilated adoption and carrying into law the document known as the People’s Charter.”

“That this meeting recommend the people of all trades and callings to forthwith cease work, until the above document becomes the law of the land.”

Troops were sent into the strike areas and by September a combination of repression and hunger, with over 1500 arrests saw the strike dwindle and consequently the movement once again. The movement held together until the crisis of 1846 accompanied by the Irish famine brought Chartism into its third period of activity.

O’Connor was elected as MP for Nottingham in 1847. With a background still of poverty, misery and starvation and also the attempt of pacification by the passing of the Ten-Hour Act, the movement tended to focus on the unemployed. In Glasgow there were severe bread riots in April 1848 and many people were killed and wounded. The Government made serious military plans.

The new tide began to arise, in February 1848, the people of Paris suddenly drove the King of France from his throne, and the people of Paris had proclaimed a Republic. One by one Royalty was under siege throughout Europe. Popular insurrections were taking place. The small kingdoms of Germany the kingdoms and Duchies of Italy, which had began to go up in smoke. The King of Prussia was forced to grant a Constitution. The Emperor of Austria accepted the National Guard forced on him, and Metternich fled to England.

In England the Chartists promptly drafted a new petition and an Assembly called to present it, a Constitution of the British Republic was drafted. A mass meeting was to be called for April 10th to present the petition, to meet on Kennington and march to Parliament. The frightened Ruling-Class thought it was to be the day of Revolution. A new petition of 1,975.000 signatures was presented. The Duke of Wellington had packed London with troops and special police.

Kennington Oval Chartist Meeting

On May 1st the Chartist-Convention (which became the National Assembly) debated the question of armed insurrection.

A National Guard was instituted as a result of a local Lancashire and Yorkshire Conference. 3,000 were reported drilling at Wilsden, under a black flag. There is evidence of other armed Chartist forces at Leicester, Aberdeen and Glasgow. London was to be the centre of the insurrection; they were in touch with Irish revolutionaries. The headquarters were in Orange Street, as it was called then, in Red Lion Square. Numerous bands of armed men were scattered about Bloomsbury, the largest number at seven dials, with pickaxes ready to turn paving stones into barricades

.

Unfortunately for the Chartists, they could not try their strength because the movement was riddled with spies and provocateurs and the executives were arrested.

Afterwards the movement went into decline despite the adoption of a new programme with marked socialist features. The National Charter Association continued until about 1858. ERNEST JONES continued almost alone. The failure of Chartism was partly because of its leadership and tactics, but also because it was new and the working class immature.

CHAPTER FIVE

THE CO-OPERATIVE MOVEMENT

The earliest Co-operatives were mainly attempts by groups of workers to break the monopoly of the millers and to provide cheap flour for their members. Examples were the Hull Anti-Mill Society of 1795 and the Devenport Union Mill of 1817. Then came Owenite Utopian Socialism and the Co-operatives were hailed as the key to the peaceful supersession of Capitalism.

The `new model’ Co-operative was that of the Rochdale “Equitable Pioneers” having founded their Co-operative shop in Toad Lane in 1844. Twenty-eight men started it with twenty eight pounds. They survived by paying a dividend on purchases. The greatest single benefit that the “Co-ops” brought to the workers was pure food. There were `sand in the sugar’ grocers, and other adulterators commonplace then.

In the 1860’s the Co-operative wholesale society came into being to supply goods to the retail societies and in the next decade it began actually to produce goods in its own factories.

In 1869 began the regular series of annual Co-operative Congresses, which has continued.

From the second congress sprang the Co-operative Central Board, which developed into the Cooperative Union, the co-ordinating body for propaganda and education. The first central board contained Owenite and trade union Junta members. Also there were sympathisers from the middle class who became less needed as time went on.

On many occasions the Co-op’s supported the wider working class movement including strike struggles.

Eventually people who had become successful traders in commerce got to the top. The belief that the movement would peacefully put an end to the competitive system, while never formally abandoned, became more of a pious dream than a reality.

The Co-operative movement took in thousands of workers who learned how to organise and administer large-scale business enterprise at the time. This demonstrated conclusively that the ability to do so is not confined to the Capitalist Class.

CHAPTER SIX

THE NEW SPIRIT AND NEW MODEL UNIONS

After 1848 there was a tendency for the narrow-minded craft mentality to become a trend due to the setbacks of the previous period.

The “New Model” Unions, as they became known, however were not Trades Unions but Trade Unions. A national organisation employed in a single craft. They expressed the point of view of the skilled artisans. The result was to go against strikes and rely upon keeping down the supply of labour by restricting apprentices, discouraging overtime and even encouraging emigration. They were exclusive, catered for a labour aristocracy and had little concern for the masses outside their ranks.

The first of the New Model Unions was the AMALGAMATED SOCIETY OF ENGINEERS founded in 1851 by merging a number of craft unions. The journeymen Steam Engine and Machine Makers and the Millwrights Friendly Society were the most powerful. The next strongest of the unions at this time were the Iron founders and Stonemasons. The Lancashire Cotton Operatives formed a permanent organisation in 1853 along similar lines. The Amalgamated Society of Carpenters, founded in 1860, became second only to the A.S.E. in numbers and influence.

In 1860, these unions formed an unofficial central leadership known as the JUNTA. The JUNTA can be described as a “Cabinet” of the Trade Union Movement. The presence in London of the headquarters of these societies brought their salaried officers into close intimacy with each other. The inner circle consisted of ALLAN and APPLEGARTH of the Engineers and Carpenters, GUILE of the Ironfounders, and COULSON of the Bricklayers.

A fifth member, GEORGE ODGER, was of a different kind belonging only to a small union of skilled Bootmakers. But he became important as the secretary of the London Trades Council and an influence in Radical circles.

ROBERT APPLEGARTH became a leading member of the FIRST INTERNATIONAL (led by KARL MARX) and its Chairman in 1870.

The “New Model” Unions brought more business methods into the working class movement and care for the more tedious details of organisation. They made trade unionism a normal and regular part of working class daily life.

The JUNTA interested itself in politics, but not in the same way as the Chartists. They were more interested in exerting pressure on the existing parties. They participated in the Reform agitation of 1866-7.

Many Existing sections did not follow the “New Model” especially the miners and textile workers and those in the north They challenged the domination of the Junta and (with the assistance of GEORGE POTTER of the London Working Men’s Association took part in national conferences, which initially were boycotted by the JUNTA until 1872 when they took a hand.

Eventually from this The TRADES UNION CONGRESS came about. In the General Election of 1874 Trade Union Leaders came forward as candidates for the first time independently of the Liberal and Tory Parties, though as individuals they were still only Radicals.

CHAPTER SEVEN

THE INTERNATIONAL

The INTERNATIONAL WORKING MEN’S ASSOCIATION, later known as the First International, was founded at an international workers’ meeting in St. Martin’s Hall, London, on September 28th, 1864.

Under the leadership of KARL MARX and FREDERICK ENGELS it was for 10 years the directing force of all the advanced sections of the working class throughout Europe.

Marx and Engels

The movement in England had always been sensitive to events abroad. Going back to the 1840’s the Chartists had taken the initiative in the formation of the body known as the `Fraternal Democrats’, a forerunner of the 1st International, founded in 1846, mainly through the efforts of GEORGE JULIAN HARNEY. The movement in Britain had therefore kept in touch with events abroad, through the great epoch of European Revolutions.

The fundamental aim of the International was the union of workingmen of all countries for the emancipation of labour. Its principles went on to declare that, “the subjection of the man of labour to the man of capital lies at the bottom of all servitude, all social misery and all political dependence.”

Between 1864 and 1870 branches were established in nearly all European Countries as well as in the United States, the majority of Trade Societies in some European Countries joining in a body. The central administration was entrusted to a General Council of 55 members sitting in London, which was composed of London residents of various nationalities, elected by the branches in the countries to which they belonged. The General Council had, however, no legislative or other control over the branches, and in practice served as little more than a means of communication between them, each country managing its affairs in its own way.

The principles and programme of the Association underwent a steady development in the succession of annual international congresses attended by delegates from the various branches. The extent to which English workingmen really participated in its fundamental objects is not clear.

In 1870 ODGER was president and APPLEGARTH chairman of the General Council, which included BENJAMIN LUCRAFT, afterwards a member of the London School Board, and other well-known workingmen politicians.

But few English Trade Unions (amongst them being the Bootmakers and Curriers) joined in their corporate capacity. When, in October 1866, the General Council invited the London Trades Council to join, or that failing, to give permission for a representative of the INTERNATIONAL to attend its meetings, with a view of promptly reporting all Continental strikes, the council’s minutes show that both requests were refused.

The London Trades Council declined indeed to recognise the INTERNATIONAL even as the authorised medium of communication with Trade Societies abroad, and decided to communicate with these directly. APPLEGARTH attended several of the continental congresses as a delegate from England, and elaborately explained the aims and principles of the Association in an interview published in the New York World of May 21st 1870.

After the suppression of the PARIS COMMUNE the branches in France were crushed out of existence and the membership in England fell away. The annual Congress held in 1872 at The Hague decided to transfer the General Council to New York and the INTERNATIONAL was unable to play any part in the English Labour movement.

The formation between 1858 and 1867 of permanent Trades Councils in the leading industrial centres was an important step in the consolidation of the Trade Union Movement.

THE LONDON TRADES COUNCIL

The Struggle over Politics.

In 1862 the London Trades Council held a great meeting in St. James’s Hall in support of Northern States against Negro slavery.

POTTER fought the Bill of GLADSTONE to sell Government Annuities for small amour as an insidious attempt to divert savings workingmen from their Trade Unions and benefit societies into an exchequer controlled by the governing classes. London Trades Council sent an influential deputation to Gladstone to publicly disavow Potter action.

Also during 1861-62 HOWELL and ODGER strove in vain to enlist the council in the agitation for a new REFORM BILL, but 1866, under the influence of ODGER and APPLEGARTH, ALLAN and COULSON, the council enthusiastically threw itself into the demonstration in favour of the REFORM BILL. The Liberal Government brought in the Bill. The council took a leading part in the agitation, which resulted in the enfranchisement of the town Artisan. In the same year the Council agreed to co-operate with the INTERNATIONAL in demanding DEMOCRATIC REFORM from all European Governments.

CHAPTER EIGHT

THE NEW UNIONISM OF 1880-1900

In 1881 FREDERICK ENGELS had publicly pointed out in the Labour Standard, Organ of the London Trades Council; (a series collected in his pamphlet The British Labour Movement) that the waning of Britain’s Industrial Monopoly meant that the unions could not maintain their organised strength. He pointed to the failure of unions, “Unless they really march in the Van of the working class…” This meant breaking the, “Vicious circle out of which there is no issue” (Of movements limited to wages and hours) and that they must cease to be the “Tail of the “Great Liberal Party.” “A Political organisation of the Working Class as a whole,” which would win power for the workers and build a new social order.

As for the dominant leaders – the “old gang” as they became to be called, this appeal fell on deaf ears. The men who succeeded the JUNTA offered the movement not leadership but abdication, they dominated the T.U.C. It was the Socialists, both the intellectual leaders outside the unions and the younger Trade Unionists, who became converts, who led the fight against the “old gang” and revolutionised trade unionism.

THE LONDON MATCH GIRLS’ STRIKE

In July 1888, a famous Socialist led strike of the girls at Bryant and May’s match factory took place in the East-End of London, it secured wide publicity. It was the “Light Jostle needed for the entire avalanche to move” (Engels). The Gasworkers followed. Unrest had been growing for some time at Beckton, where the Stokers worked a 12-Hour shift and a 13-Day fortnight. They demanded and 8-Hour shift, a 12-Day fortnight and a shilling shift wages increase. Led by WILL THORNE, a Beckton Stoker, the men vainly sought Liberal aid to have their case raised in Parliament, and then turned to the Socialists.

They were advised to organise a union and were given maximum assistance, notably by ELEANOR MARX and AVELING.

Eleanor Marx

The “Law and Liberty League” of 1887 united Socialist and Radical Working men and Trade Unionists in a broad mass movement.

Rapid recruitment to the new Gasworkers’ and General Labourers’ Union enabled the men shortly to hand in strike notices. They were in so strong a position that the Gas companies conceded the whole of their demands, save that the wage granted was 6d instead of 1/-. This led to a spontaneous strike of the men at the South West Indian Dock that within a week became a “General Dockers’ Strike.”

London Dock Strike, 1889

A movement that completely paralysed its greatest port electrified the world. Under the leadership of Socialists JOHN BURNS, TOM MANN, and BEN TILLET, with ELEANOR MARX as secretary of the strike-committee – the `starvelings’ had truly arisen from their slumbers. The strike lasted for four weeks sustained by an unprecedented wave of international solidarity.

CHAPTER NINE

THE WORKERS’ OFFENSIVE (1910-1914)

V. 1. LENIN in his article, Lenin on Britain in 1913 is quoted as saying that:

“…the masses of the English workers are slowly but surely taking a new path-from the defence of the petty privileges of the labour aristocracy to the great heroic struggle of the masses themselves for a new system of society.”

Within this period, union membership grew from 2.5 million to 4 million.

The initiative of the 1889 NEW UNIONISM was to be carried forward. TOM MANN was the leader that had emerged as the leading exponent of SYNDICALISM, which is organisation by industry, rather than by craft.

Tom Mann

In 1910 the several unions of Dockers and other Transport Men formed the “Transport Workers’ Federation”.

In June 1911 the Seamen struck work for uniform conditions at all ports and other improvements, The Dockers and Carters in Manchester struck and in July the Port of London was closed down.

Winston Churchill, Liberal Government Home Secretary reinforced the London Garrison and threatened to dispatch 25,000 troops to the docks to break the strike by doing the Dockers’ work.

Daily demonstrations of the strikers on Tower Hill were of unprecedented size, marches through the city counted up to 10,000 people.

Movements took place in other Ports, In Liverpool it almost turned to civil war. A General Transport strike with Dockers, Seamen, Carters, Tramwaymen, Railwaymen, a total of 70,000 being out. The leading figure was Tom Mann.

The Police brutally charged a monster demonstration on St. George’s Plateau causing a great outcry. Warships were moored in the Mersey their guns trained on the city. The troops were called out and two workers were shot when a crowd of demonstrators, said to be attempting a rescue of prisoners, were fired on. So alarmed were the authorities that the local territorials, which included many trade unionists and kept their arms at home, were ordered to remove the bolts from their rifles and turn them in at headquarters.

In January 1912, after the Glasgow Dockers struck the Dockers were in action again including London where 100,000 came out.

The big transport struggles of 1911 inspired the railwaymen and strikes broke out there too. Ultimatums to the railway companies from the railway unions led to threats of bloodshed from the Government of Asquith, Churchill sent troops to Manchester and other places without requistion from the civil authorities.

At Llanelly a strike demonstration was fired on and among the numerous casualties two were fatal.

200,000 railwaymen came out and industry was being brought to a standstill. An agreement was forced.

In the autumn of 1910 disputes over payment for abnormal places in the pit led to a strike of 10,000 miners employed by the Cambrian Combine in the Rhondda Valleys. The arrogant attitude of the mineowners headed by Lord Rhondda gave rise to deep resentment and there were stormy demonstrations. Metropolitan Police and troops were sent up the valleys and clashed with strikers at Tonypandy. Throughout 1911 strikes took place throughout these parts of the South Wales Coalfield.

A delegate conference of the Miners Federation of Great Britain decided to ballot for a national strike to establish the minimum wage, by March 1st the strike was complete and a million Miners ceased work. The first national miners strike proved to be the vastest labour conflict ever known up to that time in this country and the most sensational. The Government intervened, drafted a Minimum Wage Bill and rushed it through into law by the end of March.

As a result of the strike, within a year the number of trade unionists in mining had leapt by nearly 160,000 to over 900,000.

It was a new era for the workers, the British Working class would no longer be the same they had learned to fight and realised their power.

Within the country there was a “General Spirit of Revolt” which spread throughout the country.

Of utmost importance and significance at the time was a strike in Ireland, which was to influence important political developments for Irish freedom against British Colonial Rule, particularly the development of the movement, which led to the 1916 “Easter Uprising”. All of this occurred in Dublin and was not to be without effect upon the British Working Class Movement.

The Historic year of 1913 witnessed the General Strike in Dublin in August and September. The Irish Transport and General Workers Union was under the revolutionary leadership of JAMES CONNOLLY and JIM LARKIN.

James Connolly James Larkin

This fierce struggle of 80,000 Dublin Workers aroused an extraordinary response. Solidarity was symbolism in the enthusiastic dispatch through the Co-operative movement of a food ship to Dublin, and in the sympathetic strikes in which some 7,000 British Railwaymen took part.

There was a wave of unlimited police terror launched against the Dublin strikers. Two workers were killed, 400 wounded and over 200 were arrested. There was outrage and talk of arming the workers, general strikes and revolutionary action throughout the trade unions.

At the TUC in Manchester, Robert Smillie, president of the Miners federation, said:

“If revolution is going to be forced upon my people by such action as has been taken in Dublin and elsewhere I say it is our duty, legal or illegal, to train our people to defend themselves …it is the duty of the greater trade union movement, when a question of this gravity arises, to discuss seriously the idea of a strike of all the workers.”

Everything pointed to a maturing political and social crisis towards the end of 1914.

The number of disputes in 1908 averaged 30 a month. In 1911, 75 a month. The latter half of 1913 and the first half of 1914 the strike total rose to 150 a month.

The summer of 1914 was working up towards a revolutionary outburst of gigantic industrial disputes. The miners were preparing new autumn claims. The Transport Workers were organising and Railwaymen and Engineers were preparing. In 1914 an alliance for mutual aid was proposed and agreed between the Miners Federation, the National Union of Railwaymen and the Transport Workers Federation. This was to be called the TRIPLE ALLIANCE.

The ruling class were in a deep crisis; the problems in Ireland and the internal situation were grave. The English aristocrats, Tory politicians and army officers were preparing for civil war. Lloyd George said openly that with labour “insurrection” and the Irish crisis coinciding, “the situation will be the gravest with which any government has had to deal for centuries.”

They thought that if the war did not materialise quickly it could be forestalled by revolution.

The first imperialist world war came, in time to dissipate the internal crisis.

CHAPTER TEN

THE FIRST IMPERIALIST WORLD WAR YEARS

Without the collaboration of the trade union leaders, the working class could not have been tied to the Imperialist War turning workers into cannon fodder for the capitalist class.

The union leaders and the labour aristocracy had control of the machinery of organised labour. They abandoned their pre-war pledges to prevent war or to end it by revolutionary means. Only some leaders such as KEIR HARDIE and WILL THORNE condemned the war.

The general feature of 1914-18 was the development of shop leadership in place of the disarmed union machine.

In engineering the SHOP STEWARDS, already existing as card inspectors and reporters to their union district committees, were transformed into workshop representatives and leaders.

Strikes took place during the war against the wishes of the union executives. In 1915 on Clydeside, shop stewards in engineering took action for a pay increase and fifteen establishments were involved, these included large armament firms and overtime was ceased on war contracts. A ballot on March 9th led to shops coming out on strike.

The miners of South Wales struck work in July 1915 for a new agreement with wage increases. The Government intervened under the Munitions Act but 200,000 miners struck and in less than one week the Government turned about, over rode the coal owners, and conceded the main points at issue.

Out of the Clyde workers struggle emerge the SHOP STEWARDS as the core of an entirely new form of workshop organisation. Out of the strike arose the Clyde WORKERS’ COMMITTEE, pledged to resist the Munitions Act.

WORKERS’ COMMITTEES on the Clyde model were established in other centres and in 1916 the NATIONAL SHOP STEWARDS AND WORKERS’ COMMITTEE MOVEMENT was formed.

The leaders of the Clyde Workers’ Committee were WILLIAM GALLACHER (chairman and JOHN McLean (a revolutionary and agitator for Bolshevism).

John McClean

Willie Gallacher

1917 brought the Russian Revolution, which had huge repercussions. There were almost 2.5 million working days lost as a result of disputes with the shop stewards in the lead. Up to July 1916 over 1,000 workers were convicted under the Munitions Act for strike activities.

The Russian Revolution had the effect of immensely politicising the British Working Class. This was shown at the Leeds Convention in 1917, it met with the aim of setting up Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils on the model of the Russia Soviets. Of the 1,150 delegates from all section of the movement that attended, the largest single group was 371 from trade unions and Workers’ Committees. Amongst the calls at the convention were appeals for a revolutionary struggle against the war.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

THE POST WAR CRISIS

After the First Imperialist World War a revolutionary crisis was threatening capitalism. After the Russian Revolution, Britain, as well as the whole of Europe was in a mortal crisis.

THE 40 HOURS STRIKE (1919)

On Clydeside, January – February 1919, a great struggle took place, which was to be known as the 40 hours strike. Men had returned from the armed forces and also saw the return of unemployment on an even larger scale. Engineers, Shipyard and other workers united under the leadership of the Clyde Workers’ Committee. The feeling was that this was no ordinary strike and the authorities feared a rising.

The hours of labour before the war had been fifty-four, the Scottish were in favour of a 30 hour week but Emmanuel Shinwell persuaded everyone to go for a 40 hour week.

Not everyone agreed that the strike should be in February; John McLean argued that it should be postponed until March when the Miners might also be on strike.

In this strike the MASS PICKET became a new phenomena. Everyone went to the factory gate because this is where they got their information then they would march onto the next factory or shipyard until all the industries were shut.

On the first Friday of the strike the magistrates were warned to get the trams off the road and they were given a week to do so. Because the trams were still running the following Friday an incident took place where a fight broke out and it turned into a riot. The riot started in George Square and spread down to Glasgow Green. The police made a rush at the crowd in George Square, which never budged; the police were at a loss. The Chief Constable was hit and someone tore the Riot Act out of the Sheriffs hands. GALLACHER, KIRKWOOD and a number of rank and filers were batoned down and arrested. A number of ex-servicemen at Glasgow Green fought with the police, and being very disciplined, forced them to run.

Battle for George Square

Eventually Troops were dispatched to the area on the night of the riot. The troops remained in Glasgow for a week. Machine guns were placed on top of the buildings in George Square and a Howitzer in the city chambers. Tanks were placed in the cattle market.

WILLIAM GALLACHER wrote later that the preoccupation of the Shop Stewards Movement with industrial organisation alone, and their contempt for Politics, meant that, “We were carrying on a strike when we ought to have been making a revolution.”

The national union officials of the unions concerned isolated the strike and also disciplined their local officials. A 47-hour week was agreed between the employers and the trade unions.

In the meantime the miners prepared for their struggle, their demand included a 30% increase, a six-hour day and nationalisation of the mines with a measure of workers control of the industry. Since the miners were in consultation with the Triple Alliance, who had also tabled demands, also with coal stocks depleted, the Government could have been faced with a General Strike with revolutionary potential.

Lloyd George bluffed; offering a commission on the one hand and threatening armed force suppression of any strike on the other hand. The union leaders recoiled from the threat.

There were many working class strikes of Cotton Operatives, Railwaymen and others up to 1920.

HANDS OFF RUSSIA!

In August 1920 the climax of British intervention in Soviet Russia threatened to become open war in support of the invading Poles. It was seen as an attack on the movement of International Socialism and the trade union movement.

A `Hands off Russia’ campaign developed. It was in the spring of 1920 that the Poles, with British and French backing made an unprovoked attack against Russia and unprecedented actions took place.

It was the London Dockers who struck the JOLLY GEORGE – one of the many freighters loading munitions for Poland. The Dockers had the support of their union who put a general ban on the loading of munitions for use against Russia. In August, when the threat of open war came, huge demonstrations took place throughout the country.

In these days trade union battles had deeper and greater scope. With Councils of Action established and the threat of a General Strike, open war was stopped; the miners played a leading part.

NEW ORGANISATION AND A GENERAL STAFF

It became clear, in those days, that the millions of workers, like an army, needed better organisation and it needed a General Staff. Issues should not be narrow; victories should not be centred on sectional and isolated actions.

Since the formation of the Second International, of which the British Labour Party was a member, the social democratic parties did not oppose the imperialist war. They were not militant parties of the working class dedicated to the revolutionary transforming of society in favour of the working class. The fact was that they were parties that operated within the status quo, adapted for parliamentary elections and parliamentary business.

The chartists were the first attempt by the working class to form some sought of political aims and political party limited as it was to its charter and reforms. This was in itself an advance for the working class movement becoming ever more conscious of itself as a class with its own political destiny.

The Labour Party came out of this movement and also was another step for the workers, but it soon showed its colours.

The 1920’s, though, represented a new period of radicalism. Open class collisions were taking place with revolutionary actions and recently there had been the Russian Revolution. There was a need for a new party, a militant party, also one that was capable of diverting the working class movement as a whole, from the path of narrow trade unionism and converting into an independent political force. The party had to be the General Staff and at the same time a detachment of the class.

In August 1920, the British working class with leaders coming from the Socialist Movement, Shop Stewards Movement and Trade Unionists, formed their General Staff, the Communist Party of Great Britain, which was to serve the movement for 30 years or more.

Side by side with these developments there took place a series of amalgamations. The grouping of the numerous unions of Dockers and other transport workers in the Transport Workers Federation gave place in 1921 to their fusion into the TRANSPORT and GENERAL WORKERS UNION. It became the largest single union, sharing the field of general labour with the NATIONAL UNION of GENERAL and MUNICIPAL WORKERS. The latter was a descendent of the Gasworkers Union of 1889. Absorbing a number of leading craft unions created the expansion of the AMALGAMATED SOCIETY of ENGINEERS into the AMALGAMATED ENGINEERING UNION in 1920.

Unfortunately during the next few years it became clear that the labour chiefs and the labour aristocracy were to disrupt the movement. The Capitalist class were, out of their imperialist profits plundered from the colonies, still in a position to bribe, corrupt and foster the labour aristocracy. This social stratum had been nurtured because it “did all right” out of capitalism, it was “dazzled” by the glitter and that is why it supported the war, because it was imperialist bribed and imperialist corrupted.

The labour aristocracy was only too willing to compromise the struggle.

With the onset of the 1921 slump, the employers set out to push the burden of the crisis onto the backs of the workers. They set out on an offensive. In the face of it the labour traitors were to hold back the movement through misleadership.

The capitalists were first to take on the vanguard of the working class -The Miners. They wanted a return from national to local agreements and also wage-cuts.

The Miners Federation invoked the aid of the Triple Alliance unfortunately the leaders were not enthusiastic and they took a colloquial attitude. Strike notices were postponed. Leaders of the Miners’ Union also capitulated and the time of the sell out became known as “Black Friday”.

When the Labour Government of Ramsey MacDonald took office in January 1924, a railway strike was in operation over wage cuts. The Locomotive men had rejected wage-cuts under A.S.L.E.F. but the N.U.R. had accepted the cuts on behalf of the drivers. The division brought bitterness. The Labour Government hastened to say in the House of Commons that it had no sympathy for the strike. The government also tried to put pressure on the Dockers in February.

An important move was made at this time to try and deal with the situation on behalf of the working class. The veteran TOM MANN led the formation of the NATIONAL MINORITY MOVEMENT in London in August 1924 and became its president.

The aims were not against the unions or for disruption of them or to encourage new unions. The object was to unite the workers in the factories by the formation of factory committees and to work for the formation of one union for each industry. Also to strengthen the Trades Councils to be representative of every phase of the working class movement, with its roots firmly embedded in the factories of each locality. It stood for the creation of a real General Council which would have the power to direct, unite and co-ordinate all of the struggles and activities of the trade unions. To make it possible to end the present chaos and go forward in a united attack in order to secure not only the immediate demands, but to win complete workers’ control of industry.

The movement first took root in the coalfields (notably South Wales and Fife) and recorded support for the Red International of Labour Unions (founded in Moscow in the summer of 1921. A Miners’ Minority Movement developed during 1923 and A. J. Cook became secretary of the M.F.G.B. upon the enforced resignation of Hodges due to the campaign of the minority movement.

The labour Government was defeated and the TUC General Council at Congress was given powers to intervene in disputes in 1924.

CHAPTER TWELVE

THE 1926 GENERAL STRIKE

In 1923-24, the coal industry was heading for disaster. The Prime Minister, Baldwin, demanded wage reductions of all workers to, “Put industry on its feet.”

The owners’ demands on the Miners were rejected by the Miners Federation of Great Britain (M.F.G.B) and had the TUC General Council support. A special support committee was set up with assurances from the railway and transport unions.

Miners Federation of Great Britain

Detailed preparations were made in the event of a Miners’ lockout. They met on July 30th 1925, the day before the official notices were due to expire. The Government, unprepared for such a development beat a temporary but hasty retreat, this was to become known as Red Friday. A nine-month subsidy was granted.

The Government preparations were immediate. Official support was given to the organisation for the maintenance of supplies, a volunteer strike – breaking organisation. Blackleg shock troops were given technical training.

Counter preparations were not made on the trade union side. Some key traitors were moved into positions on the General Council of the T.U.C. Attacks on Communists were taken into the unions. Within a fortnight the Government swooped and arrested 12 Communist Party leaders, advocates of preparedness. They were jailed after a big state trial.

A Royal Commission report was produced on the coal industry that was vague about state intervention in the coal industry. This was intended to sew confusion and splits, but it was definite that the miners should accept longer hours or lower wages.

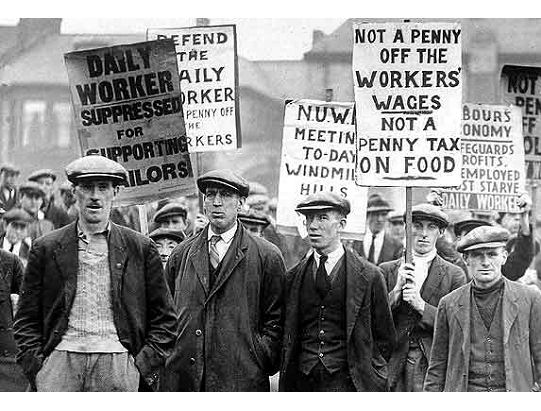

The M.F.G.B. line, supported heavily by the Communist Party Newspaper, The Daily Worker, was, “Not a Penny off the Pay, Not a Second on the Day.” The T.U.C held a defeatist view not shared by the Miners who stood firm at their delegate conference on April 10th.

Also the Minority Movement held a conference of action attended by 883 delegates representing around a million trade unionists, supporting the militant position.

The coal owners soon announced their intention to proceed with negotiations at a district level only and demanded sweeping wage reductions.

The T.U.C. were forced to harden their attitude in support of the Miners. On April 27th decided to draft plans for action, yet they still were bemused by the Royal Commission report.

A General Strike Order was drafted and was endorsed by a conference and unions representing over 3,600,000 members against a handful representing 50,000. It was announced that the trades specified would strike from midnight on Monday May 3rd.

The call out was in two grades or lines. The first line was all transport, printing (including newspapers), productive industries (iron and steel, metal and heavy industries) and building (except housing and hospitals). The second line was engineering and shipbuilding.

Individual Unions were asked to place their powers into the hands of the General Council after the call out. The maintenance of food and health services was to be undertaken by unions.

The General Council thought that it was empowered to settle on behalf of the Miners, the M.F.G.B. protested vehemently against the Industrial committee’s re-opening of negotiations with the Government within a few hours of the strike decision.

The General Council basically accepted the Royal Commission’s report.

When the Daily Mail Printers struck as a result of anti-union propaganda, Baldwin called it an “overt act of war”. He demanded the unconditional withdrawal of General Strike notices if negotiations were to continue.

The T.U.C. was in a war it did not want to be in and feared to win. It feared more the strikers; the working class might win in a revolutionary fashion.

The General Strike took place at midnight on Monday May 3rd as decided previously. It happened despite a defeatist leadership. By the end of the first week the General Council’s attention was concentrated not on leading the strike but on negotiations to end it. On Wednesday morning, May 12th, the Council, in a humiliating way, announced their unconditional capitulation. The T.U.C. organ the British Worker suppressed the M.F.G.B. repudiation of the call-off.

Immediately the employers hit back determined to reduce wages, impose non-unionism and servile conditions. But the strikers themselves continued. The Nine Days of action made the workers feel its own power. They proved that the men and women were capable in an emergency of providing the means of carrying on the country. It also proved something to the sold out leaders, “Never Again” was to be their slogan. Arthur Henderson was subsequently to call it the “terrible prospect” of a collapse of the present social and political order.

The General strike was over by the middle of May, but the Miners remained stubbornly on strike until December, even at the end rejecting surrender, which now involved the loss of the seven-hour day as well as the wage cuts.

Colliers on Strike in 1926

The failure of the General Strike was due to a number of circumstances and important lessons can be drawn from the experience.

The Capitalists class led by the Conservative Party was more experienced and organised than the workers and their leaders. They were fully armed and prepared and they struck their blows at the decisive points of the struggle.

On the other hand the General Staff of the labour movement, the T.U.C. General Council and its “political committee” the Labour Party were demoralised and corrupt. They were downright traitors to the Working Class. They were Thomas, Henderson, MacDonald and Co. with spineless fellow travellers Purcell, Hicks and others.

The Capitalist class knew that the fight had to be fought politically because the strike had enormous political importance and therefore measures of a political character had to be taken. Therefore the authority of the King, House of Commons and the constitution would have to be invoked. There would need to be a state of emergency and troops would have to be used.

The General Council of the T.U.C. would not recognise the political realities of the situation and insisted that the General strike be of an economic character. It had no intention of turning the struggle into a political one or raising the question of political power. It therefore doomed the strike to inevitable failure.

A General Strike, which is not turned into a Political Struggle, must inevitably fail.

The General Council refused to accept International support. It refused to accept financial assistance from the workers of the Soviet Union and other countries. It also meant that the strike was not made an action in the struggle of the workers of all countries. Also, the fact was that the Amsterdam federation of Trade Unions did not aid the General Strike but reduced support to resolutions and platitudes. The social democrats of the Second International and the connivance of the trade unions of Europe and America donated not more than one eighth of the amount the trade unions of the Soviet Union were able to afford. In fact the Amsterdam Unions literally acted as strike-breakers by allowing transport of coal to break the strike.

There is no doubt that the weakness of the Communist Party played a role of no little importance. Even though its attitude was correct, its prestige and influence was small.

The outcome of the strike showed the unsuitability of the old leaders, the collaborators and compromisers. The necessity was that new, revolutionary leaders should replace them.

The task of the Communist Parties was to convert the attacks of the Capitalists into a counter attack of the working class, for the abolition of capitalism.

******

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Webb, Sydney and Beatrice, The History Of Trade Unionism.

Hutt, Allen. British Trade Unionism (A Short History).

Glasgow 1919. (The Story of the 40 hours Strike with an introduction by Harry McShane). The Molendinar Press.

Morton, A.L. A Peoples’ History of England.

Cole, G.D.H. The British Common People.

Lenin, V.I. Lenin on Britain.

Marx, Karl and Engels, Frederick. Selected writings and correspondence. Engels, Frederick. The British Labour Movement.

*******************************

For more information on John Doherty, who tried to establish a cotton spinners’ union in Manchester in the 1830s, see http://radicalmanchester.wordpress.com/2009/08/12/john-doherty/

Thanks for the contribution, Sarah.

Very interesting, Thanks! What a noble struggle undertaken by working people against enormous odds. But what now? How do we organise in todays technological society?

Pingback: The Legacy of Eleanor Marx – Jacobin Dev